BELLAIRE, MI – Where to find morel mushrooms is a question akin to asking a state secret, even in Northwest Michigan, where their mycelia are so abundant there are two competing morel festivals held here every spring.

That’s why I called up James Dake, Education Director for the Grass River Natural Area. He teaches a public workshop on morel foraging, so I was pretty sure he’d be willing give me the low-down on where to look. He was kind enough to meet me for a walk in the woods and introduce me to this stunning 1,492-acre park, which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year.

“Getting your morel eyes on,” requires combining a zen-like state of mind with a scrupulous attention to detail before their wrinkled brain/sponge shapes pop forward from the leaf litter, like nature’s own “magic eye” poster.

Its origins were of ecological crisis. Fifty one-years ago, in 1968, a developer badly screwed up some sensitive wetland habitat in this ecologically fragile corner of Northwest Michigan, near the top left of “the Mitten.” The public outcry at the destruction – and the contrition of the developer, it should also be noted – led to the creation of this non-profit and government partnership that protects the river and wetlands that connect Lake Bellaire with Clam Lake. The two lakes are two among fourteen interconnected bodies of water in Antrim County’s “Chain of Lakes,” shown on the map below.

The park’s property is also where I dug my first ramps, the mild and wild onions that, along with morels and fiddlehead ferns are spring’s edible harbingers. Wild foods can be collected by the public without permit in Michigan on state lands or parks, in national forests, and on private land with owner permission.

In fact, foraging is so widespread in woodsy Michigan that the state now offers a certification in conjunction with Midwest American Mycology Information, in mushroom identification. The certification isn’t required to gather and sell the mushrooms of Michigan’s woods, including the most common: morel, oyster, sulfur shelf, and chanterelles, though it is both a federal and state requirement that all wild-collected mushrooms be inspected and signed off on by a mushroom expert prior to sale.

Since there are more than 560 certified foragers now combing Michigan’s woods, it might as well be compulsory, though. Restaurant owners and chefs understand that while wild foods on a menu command a premium with locavorious diners, the repercussions of having a poisonous mushroom make it to a diner’s plate would be severe. It’s no surprise they prefer to opt for certified ingredients.

We found the ramps when Dake took me for a short mushroom hunt, though we were hurried, and at least in my three decades of hunting experience, expertly camouflaged morels are less likely to reveal themselves during periods of brisk walking and jumpy glancing. “Getting your morel eyes on,” as my sister Michelle calls it, requires combining a zen-like state of mind with a scrupulous attention to detail before their wrinkled, brain/sponge shapes consent to pop forward from the leaf litter, like nature’s own “magic eye” poster. (Hunting success also requires morels be present, though James informed me they were there all along in a triumphant text the next day.)

Although we got skunked on morels, as we were walking along, Dake pointed to a patch of deeply green two-leaved plants and explained they were ramps, a wild onion that can be cooked, eaten raw, or pickled, all three of which I did later that day while making my “Michigan Meal” of hunted and gathered ingredients.

He bent down and it took him longer than I thought it would to pull up the ramp. He explained that you have to dig them out thoroughly or the delicate green-onion-like bulb will snap off, leaving you with only the (still delicious) leaves. The cutting board photo below shows that most of the time I came away with the bulb but a couple times I did not.

Fun fact: Chicago, where I currently reside between wanders, was named for the wild ramp, which local native tribes called shikaakwa (chicagou) and which grew then in abundance near Lake Michigan.

Even though I really appreciated the foraging trip, I have to say I was even more impressed with the park, which packs nine different habitats into one biodiversity mecca featuring 500 species of plants, 147 species of birds, 35 species of fish, and 33 reptiles and amphibians, some endangered or threatened.

Basically, Grass River is your ticket to Northwest Michigan’s ecology in concentrate form. Nine habitats include rare northern fen, northern wet meadow, rich conifer swamp, poor conifer swamp, hardwood conifer swamp, emergent marsh, northern shrub thicket, mesic northern forest, and dry-mesic northern forest.

Check out this recording of river otters, captured in the park by their own cameras, an indicator species that demonstrates that the environment is completely pristine.

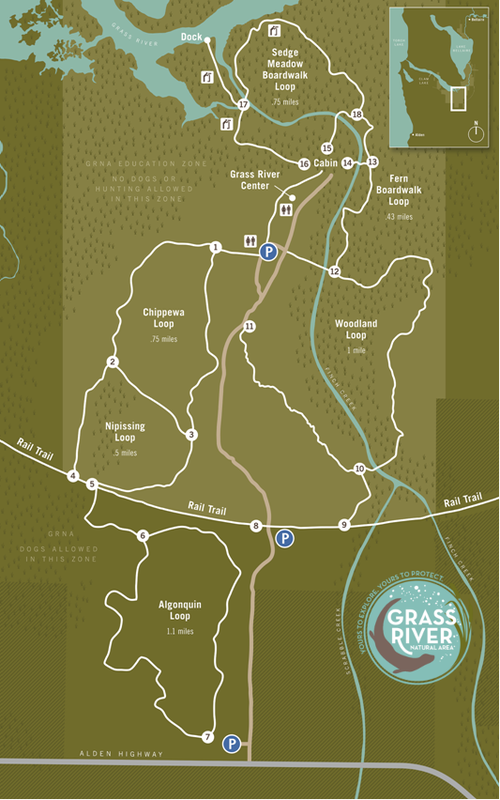

The park is open 365 days a year dawn to dusk and offers seven miles of super well-maintained trails – 1.5 miles of which are floating! The gently bobbing boardwalk allows visitors access to rare cedar wetland and northern fen, which would otherwise require a boat to experience.

A fen, like a bog, is an area where the water table comes very close to the surface of the soil but doesn’t overtop it. The main difference is bogs get their water and nutrients from rain, while fens are fed by springs or other surface waters.

This panoply of wildness is all catalogued in a field manual that James Dake wrote. He was kind enough to gift me a copy, sales of which support the educational mission of the park.

Things you can do at Grass River besides hiking and birdwatching include some extremely serene and wild paddling (you’ll have to bring your own kayak/canoe or use an outside vendor) bicycling and cross-country skiing. Dogs are allowed on trails on leashes. I can’t recommend the park more highly – whether you’re packing in a picnic or scouring the woods for wild fresh foods to take away.

***

Directions to Grass River Natural Area (Google Map to GRNA)

The Grass River Natural Area entrance is at 6500 Alden Highway (Co. Road 618), 4 miles northeast of Alden, 6 miles south of Bellaire and 8 miles west of Mancelona. The preserve is also accessible by boat from the Grass River dock located on the south end of Grass River between Clam Lake and Lake Bellaire.

Sources:

Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development

One Comment Add yours